“I love it when plans come together” said John Hannibal Smith and perhaps Tadej Pogačar thought so smiling on the podium after his unchallengeable victory in the Giro. But our carefully laid plans are often twisted and ruined by a reality that reminds us that we live surrounded by disruptive events. This was expressed regretfully by Matteo Jorgenson in his statements after the massive crash that occurred in the fifth stage of the last race. Dauphiné Liberé. A Jorgenson who days later threatened Primož Roglič’s triumphant plans in the same race, in a memorable final stage brilliantly executed by Ineos.

This is not the first time that we have emphasised the uncertain circumstances that make up cycling events, the importance of team adaptation and leadership structures to respond to these circumstances. We have extended these reflections to our meetings and lunches, concluding with the curiosity to empirically verify the role of leadership structures in the victory of a cycling team in its most important competition: the Tour de France.

When Movistar showed up to the Tour with the legendary trident Landa-Nairo-Valverde, the most circumspect fans raised an eyebrow of skepticism at three leaders, while the most sanguine ones mocked what they called eusebiades (by Eusebio Unzue, the team’s magician). They were a generation of followers who had been fed the stories of the Tour of the great leaders of the past, its legends. Fausto Coppi was asked by his gregarious every morning: what are you in charge of today, captain? And one of them, Sandrino Carrea, the most faithful of his soldiers, cried on the podium of the 1952 Tour dressed in yellow thanks to a distant breakaway and looked for Coppi with his eyes as if to apologize and tell the campionissimo, this jersey does not belong to me. Merckx was a tyrant with the entire peloton and with his team, like Armstrong or Chris Froome and in his own way, even Indurain or Marco Pantani. The team was for them, and if they failed or fell, there was no more. There was no second in the team or plan B. The change that the three-headed Movistar anticipated, the pandemic made it the norm and Jumbo refined it with its dominance in the last Vuelta, turning the victory into a team game between Roglic, Vingegaard and Kuss . An intermediate step from a centralized leadership to a decentralized one began to be taken by the largest teams—Sky, Ineos, Jumbo, UAE—when they decided that the leader’s lieutenant or even the third in the team would not lift his foot once his task was finished. and he let himself go saving his strength for the next day, but rather he continued to strive as if he were the leader so as to have one more tactical weapon in case of a fall or failure of the boss.

The specialized literature differentiates between centralized and decentralized leadership structures. Centralized structures are organized around a single leader, and the rest of the team members subordinate their actions to the requirements of the leader, enabling and reinforcing said leadership over time. Alternatively, decentralized structures are organized around several leaders, in which the leadership role alternates over time between several team members who move flexibly between follower and leader roles, being leaders or team members depending on the circumstances or changing task requirements. If you ask yourself which is better? the answer is that it depends on the team’s experience with the task it performs and its context. When the team understands its task as simple, with few changes and the context in which it is performed is predictable, centralized structures usually allow objectives to be achieved very efficiently. But when the team understands its task as complex, notices many changes and its context is unpredictable, decentralized leadership structures offer more flexibility and adaptability for the team to achieve its objectives.

Thus, to predict the performance of the teams in the Tour we select several variables: the quality of the team (total UCI points of the team members), the initial leadership structure (number of leaders at the beginning of the test), the leadership structure during (number of leaders during the development of the test), qualitative disruptive events (whether the leader or leaders had suffered a fall, injury, injury or abandonment) and quantitative disruptive events (number of abandonments that occurred in the team, not including the leader(s). The initial leadership structure and during the test were inferred from our news analysis, while the rest of the variables were obtained from the platform. ProCyclingStats. In particular, we obtained the performance measure from ProCyclingStatsScore (PCSS) of the 22 member teams in the selected editions (23 in the 2021 edition). The PCSS is a synthetic index that combines stage victories, days in the general classification, days with the regularity jersey, days with the mountain jersey, days with the white jersey, the number of stages in those in which its runners finish between the top three and ten, in addition to the days in the race of the best overall runner. For our analyzes we select the period between 2018 to 2023 (including both). In 2017 the calculation of UCI points changed and the number of members in the Tour teams was reduced from nine to eight and both modifications could affect the results.

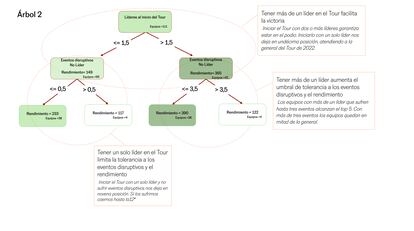

We use decision trees, an algorithm machine learning A supervised model that generates a set of rules for making decisions. Decision trees work in two steps: first, they generate a model based on the data with which it is trained and second, they offer decision rules with a result that allows predictions to be made with new data in the future. We use this technique because it is easy to visualize (as an inverted tree), understand and interpret, making it widely used in decision-making processes.

Using this analytical logic, we trained two models represented as tree 1 and 2 respectively. Tree 1 summarizes a first model that uses all the chosen predictor variables to estimate their effect on Tour performance, and clearly shows us the role that team quality has on Tour performance. According to the regression analysis associated with the decision tree, 35% of the performance in the race is explained by team quality (UCI points). No surprises so far, a high-quality team will perform at a high level.

Considering the role of team quality on their performance in the Tour, we trained a second model controlling the quality of the teams; that is, making it equivalent between them (something that could make some sense among the first teams in the general classification), to observe how the rest of the variables behaved when predicting performance. The generated model explains a lower percentage of variability in performance by subtracting the variable with the most weight, but its simplicity offers interesting complementary observations, as tree 2 summarizes.

The analyses carried out using archival and historiographical data allow us to draw three conclusions:

First, we need a team made up of excellent riders to win the Tour. Having more than 7,900 UCI points is only within the reach of the best teams in the peloton, such as UAE, Visma, Red Bull, Ineos, Lidl-Trek, Alpecin, Soudal or Bahrain. But quality is not enough, because very good teams (with more than 7963 UCI points) obtain better results if they face more than one disruptive event during the test. This tells us about the concept of antifragility, which captures how teams improve by adapting to adversity and suggests that winning the Tour has more to do with adapting to disruptive events than with being fortunate enough that they do not occur. It’s winning, versus being in the top five.

Second, starting the Tour with decentralised leadership structures improves the performance of teams in the race. This effect is seen both in good teams (more than 6900 UCI points) and in more modest teams (less than 3680 UCI points). Therefore, a team like Ineos, starting the Tour with a decentralised leadership structure would finish in the top five, even with a chance of a podium, instead of finishing around eighth place. Similarly, more modest teams like Total Energies or Astana, starting the Tour with decentralised leadership structures could finish in the middle of the table, instead of at the bottom. It is a noticeable difference.

Finally, teams with decentralized leadership structures increase their tolerance threshold for disruptive events. It is surprising to see how the performance of decentralized structures with up to three abandonments is greater than that of centralized ones without suffering disruptive events. We are talking about finishing the overall in fifth or ninth position. In theory the performances should be equivalent, but the Tour is very tough, full of unexpected events, and rewards decentralized leadership structures that facilitate adaptation. We see this best by seeing how teams with centralized structures that suffer disruptive events fall to twelfth position overall. Centralized structures limit team adaptation and result in suboptimal performance.

These results are a first step to understand the role of leadership structures and disruptive events on performance in cycling teams. Our data do not allow us to observe the adaptive processes that occurred in the analyzed teams, the events they have experienced or their actual leadership structure. Perhaps this approach will spark interest in the platoon and future research will allow us to learn more about it.

We are not dedicated to betting, nor do we intend to win the game at the corner bar. But considering the results obtained with our trees, here is our prediction: The Tour will be won by a team that has more than 7900 UCI points, more likely if it starts with a decentralized leadership structure, even suffering a couple of disruptive events. The winning team must have a compact lineup, without major differences between its riders, shown in the median of UCI points with which the 22 teams start the race in Florence. The low median would exclude from the general classification Alpecin of Philipsen and Van der Poel, Lotto of Van Gils and De Lie, and Soudal of Evenepoel and Landa. The UAE of Pogačar, Adam Yates, Almeida and Ayuso presents an extraordinary 22,910 UCI points, almost triple the threshold of excellence; and, of them, 9,513 belong to the Slovenian, who alone owns more points than 18 entire teams. The quality is yours, but our model, however, confirms the intuition of the fans and reinforces the Visma of Vingegaard, Jorgenson and Van Aert, which is clear about the logic of decentralized leadership and has already begun its adaptation when suffering a disruptive event ( Kuss’s covid) before even starting the Tour. The third team should emerge from the duel between the Ineos of the four good guys with Rodríguez, Thomas, Pidcock and Bernal, and the Red Bull of Roglic, Vlasov and Hindley.

Let the road say the rest… Live the Tour!

Ramon Rico Muñoz He is a professor of Business Organization at the Carlos III University, Madrid.

Ramon Rico Cuevas He is a PhD student in AI and Data Science, Utrecht University (The Netherlands)

You can follow The USA Print in Facebook and xor sign up here to receive our weekly newsletter.

_